If this is your company, CONTACT US to activate Packbase™ software to build your portal.

“I’m proud to have the privilege of working for a company whose environmental efforts are characterised by both a long-term approach and a sense of responsibility,” comments Anna Mårtensson, Environmental Manager at Iggesund Paperboard’s Swedish production facility, Iggesund Mill. “Today our environmental impact is almost non-existent compared with the situation just over 50 years ago.”

When Iggesund built its first pulp mill in 1916, environmental legislation did not exist and companies were basically free to release fibre waste and chemicals into the air and water. During the mill’s first 50 years this caused a significant negative effect on the local environment. The first emissions limits were set in 1963, symbolically the same year that biologist Rachel Carson’s famous book about the influence of pesticides on nature, Silent Spring, was published and became the alarm clock that laid the foundation of today’s environmental movement.

“By the mid-1960s the combined emissions of process chemicals and cellulose fibres had turned the seabed around the mill into a desert,” Mårtensson continues. “The water smelled bad and was a brownish colour. Sensitive species at the top of the marine ecosystem’s nutrient chains had disappeared from the mill’s vicinity.”

Since the 1960s the mill’s effect on the local environment has continually been improved, driven by both economic and environmental demands. Today’s processes make more efficient use of the timber raw material, leading to a better use of resources and less release of organic material. Today having chemical emissions at the levels of the 1950s would be inconceivable; instead, more than 99 per cent of the process chemicals are recycled. Since the 1970s, Iggesund’s water purification measures have been built up into a three-stage process: mechanical, biological and finally chemical purification almost identical to that used to produce drinking water.

“Experts say the solution we have at Iggesund Mill is the best available technology,” Mårtensson adds. “Above all, it has radically reduced our emissions of sulphur and phosphorus, which are particularly important since our water goes out into the Baltic Sea, which is threatened by eutrophication.”

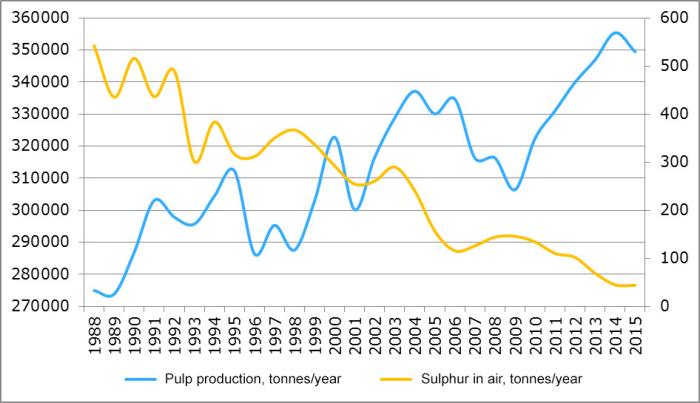

The mill’s airborne emissions have developed in the same direction – the levels of acidifying sulphur or eutrophying nitrogen are down to levels where their local environmental impact is hard to document.

“People can catch edible food fish in the water surrounding the mill,” Mårtensson says. “Using chemical analysis it is impossible to distinguish those fish from fish caught in reference areas far from industrial sites. We are very pleased to see how species like sea eagles and seals, which had disappeared from near the mill, have now returned.”

Sulphur emissions are one example of how the systematic environmental work has developed over time. In 1988 Iggesund Mill emitted 1.98 kilos of sulphur per tonne of pulp produced. Today’s emissions are just over six per cent of that, at 0.13 kilos per tonne. The corresponding value for the total amount of sulphur emitted per year has gone down from 540 annual tonnes to about 44 annual tonnes. This means that total sulphur emissions have fallen by 92 per cent despite a 25 per cent production increase over the same period.

In the past five years Iggesund Paperboard has also invested SEK 3.4 billion (EUR 360 million, GBP 225 million) to make its facilities in Sweden and the UK almost entirely fossil free by switching the energy source at the mills in Iggesund and Workington to bioenergy.

In the summer of 2016 Iggesund applied for a new permit for its operations. As a first step the company wants to increase its pulp production by 40,000 annual tonnes. In a later step, Iggesund Mill wants to increase its pulp production by another 40,000 tonnes and its paperboard production from today’s 400,000 tonnes to 450,000 tonnes per year.

“We’re now starting discussions with the authorities and I believe we have a number of good arguments going into the negotiations,” Mårtensson concludes. “Not least because we can point to half a century of continual improvements.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)